Our earliest memories can be traced back to the familiar sounds, smells, and feel of our childhood homes. From the comforting aroma of mom preparing dinner to the unforgettable stories grandma told, these enduring memories trigger a sense of nostalgia that form the building blocks of consciousness and continue to impact our foundational roots and concept of self. It’s impossible to disentangle our fond memories from who we are today—and how we continue to grow and evolve.

The term nostalgia derives from the Greek words algos and nostos, meaning to reach some place, escape, return, or to get home. One of its earliest definitions can be traced back to 1726, “a morbid longing to return to one’s home or native country” and even “a severe homesickness considered a disease.” Many immigrants and their successors, especially Armenians, experience this nostalgia tied to this yearning for the home they’ve imagined or have been exiled from—whether it be the romantic version of Armenia they’ve grown to feel connected to or their respective homes scattered throughout the Diaspora: Lebanon, France, Syria, Turkey, Argentina, or beyond. Yet, no matter where one hails from, that sense of nostalgia is just as commanding, urging people to uphold Armenian traditions and values.

According to the Institute of Family Studies, nostalgia refers to even minor, but cherished, encounters that eventually become sources of savored experiences to which people are deeply connected. Nostalgic memories are always social, involving family, romantic partners, or close friends with overwhelmingly positive or complex emotions. These memories typically involve comfort senses, like traditional music, family gatherings, or shared meals—which is felt even more fervently in ethnic Armenian homes.

Cultural anthropologist Susan Pattie has devoted her research to the study of Armenian diasporas and the notion of the Armenian homeland, or hayrenik. She wrote, “The key phrase concerning Armenian dispersion and omnipresence is equivocal: it conveys pleasure at meeting a new Armenian but often and at the same time also dismay that both parties should be so far from home.”

The longing for home continues to plague people today, only strengthening nostalgic sentiments. Studies have found that those who report high levels of nostalgia are more motivated to pursue social goals, have a greater desire to be around other people, and have more ambition to resolve problems—which is why feelings of loneliness can provoke this nostalgia Pattie describes, prompting a pining for hayrenik.

For Armenian households, many can share universal sense memories that trigger this potent nostalgia. Almost all can remember a matriarch in the family cooking a traditional dish or inheriting Genocide stories from an elder in the community. Many share the experience of going to long-winded Badarak services or fumbling through the Armenian alphabet as a child in Saturday school.

These early exposures to Armenianness by the senses evoke feelings of security, familiarity, family, and community—regardless of one’s country of origin. For some, these memories shape and embody their Armenian identity today, whether it be a feeling of comfort with family and community or one of isolation or discrimination.

The AGBU editorial team has gathered snippets of the Armenian identity told through the senses, some that embody the Armenian experience tied to family and identity and others that capture this nostalgia for home.

I Ask You, Ladies and Gentlemen

By Leon Surmelian

Ladies and gentlemen, I ask you what you can do on New Year’s Eve in free and happy America, when your playmates and schoolmates, the kids you grew up with, your companions in grief and joy, in hunger and misery, fellow dreamers during your dream age, are gone, lost? What can you do when you see mountains carrying silver shields and lances, or holding eternal war council on the watershed of the Caucasus—hoary warriors with white, pointed beards guarding the boundary line between Europe and Asia? What can you do when you see the old swimming hole in far-away Pontus, seeds of ripe pomegranate, the purple cascade of the noble wisteria over porches and doorsteps, yellow roses climbing garden walls, and can hear the melancholy cry of popcorn vendors on winter nights? What can you do when the pretty girls you loved in kindergarten and grade school are dead and their bones lied unburied, or are in captivity, forgotten by their own nation?

I don’t like to drink, ladies and gentlemen. I assure you that I have no constitutional craving for alcohol, which I consider one of the worst enemies of mankind. But once in twelve months, on New Year’s Eve, I must forget my past, the New Years of long ago. I’m an American citizen, ladies and gentlemen, sincerely attached to the Constitution, and I’ll fight for America, any time, but I ask you, how can a guy forget his childhood? There are millions like me, tonight, in free happy America, haunted by their early years, which are always, everywhere, the happiest.

I’m sorry to have made such a fool of myself, and I only wish I could tell you what’s bothering me, here, deep in my heart. The world is full of sorrow and memories, ladies and gentlemen, of stories that cannot be told, of poignant images that have no stories. Forgive me, ladies and gentleman, but I must have another drink.

The book I Ask You, Ladies and Gentleman is available through the Armenian Institute Bookshop, NAASR, Amazon and Abril Bookstore

Where are You From?

No, Where are You Really From?

By Sophia Armen

When we dance

as preteens

me and my best friend

children

hold big arms spread

hands up over head

take the male side during Tamzara

Pull out a napkin and lead the shoorchbar chain

Break the inner circle of old men in the Halay

Take off our heels and throw them off the dance floor

Dance until our toes are blistered and pulsing

Clap on one knee for our fellow sisters

As the elders stare

And our parents

Chase after us telling us to look at the underside of our feet

My mom yells, with a smile, “where are your shoeeeeeees Sophia!”

At weddings

And Sunday school

And camp

And every single celebration

Of us Armenians being alive

And here we are

Two rough and tumble girls

Claiming

Our ground

Our land too

Excerpt from We are All Armenian—Voices of the Diaspora, available from the University of Texas Press online bookstore

To the Bone

By Arman Kaymakcian

Somewhere lost in my bones, lives the memory

Of lamb dinners with you and my uncles at the Armenian Royal.

I love the way the light dims, reflecting off of the worn out maroon edges of the dinner plates.

Our pilaf abundant as it spilled off of the fork onto the carpet, reminiscent of Persian village Serapi, Beautiful burgundy, gold, amber, diamond, Weaved and tied together in knots like Armenians and Turks, like Christians and Muslims, like memory and pain.

Tiny threads of pasta, mixed together with the white fluffy rice, nutty, buttery, savory, delicious.

The laughter seems to replay in my memory just like your smile in some kind of sweet slow motion, where time doesn’t matter.

Our ancient language sounding sweet surrounded me in a multitude of familiar utterance as I got lost struggling to find my way, through the thickness of the rolling rrr’s, dz, sounds and the gh that mysteriously found its escape out the mouth from somewhere deep in the back of the throat.

Pull the curtains back, and play the Armenian, Greek and Turkish sounds of the bazooki, on the stereo behind the bar.

While grandpa dances to the rhythm of the drums, as his wrists spin and the fingers snap.

I lock eyes with you then uncle Jirayir, then uncle Arax, as you rescue the Ilik (marrow) from the bones of the lamb.

A slurp from the animal bone, a shared satisfaction, as you all join in the delicacy.

Now that you’re gone, when the meat falls apart at my fork, and the hot tomato broth from the tas kebab touches my lips, it cuts to the bone.

One slurp of the marrow and the memory is found, and it’s like

you never left.

To follow Arman Kaymakcian go to Instagram @arman_kaymakcian

The Map of Her Prayers

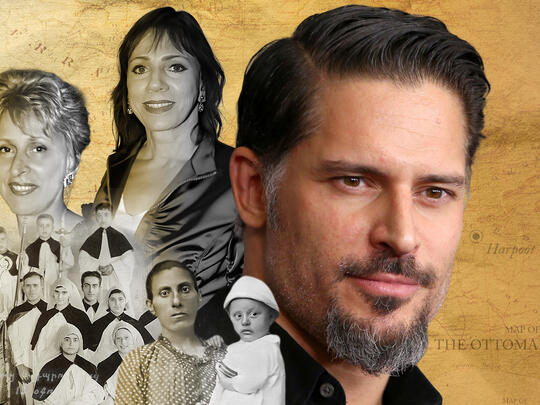

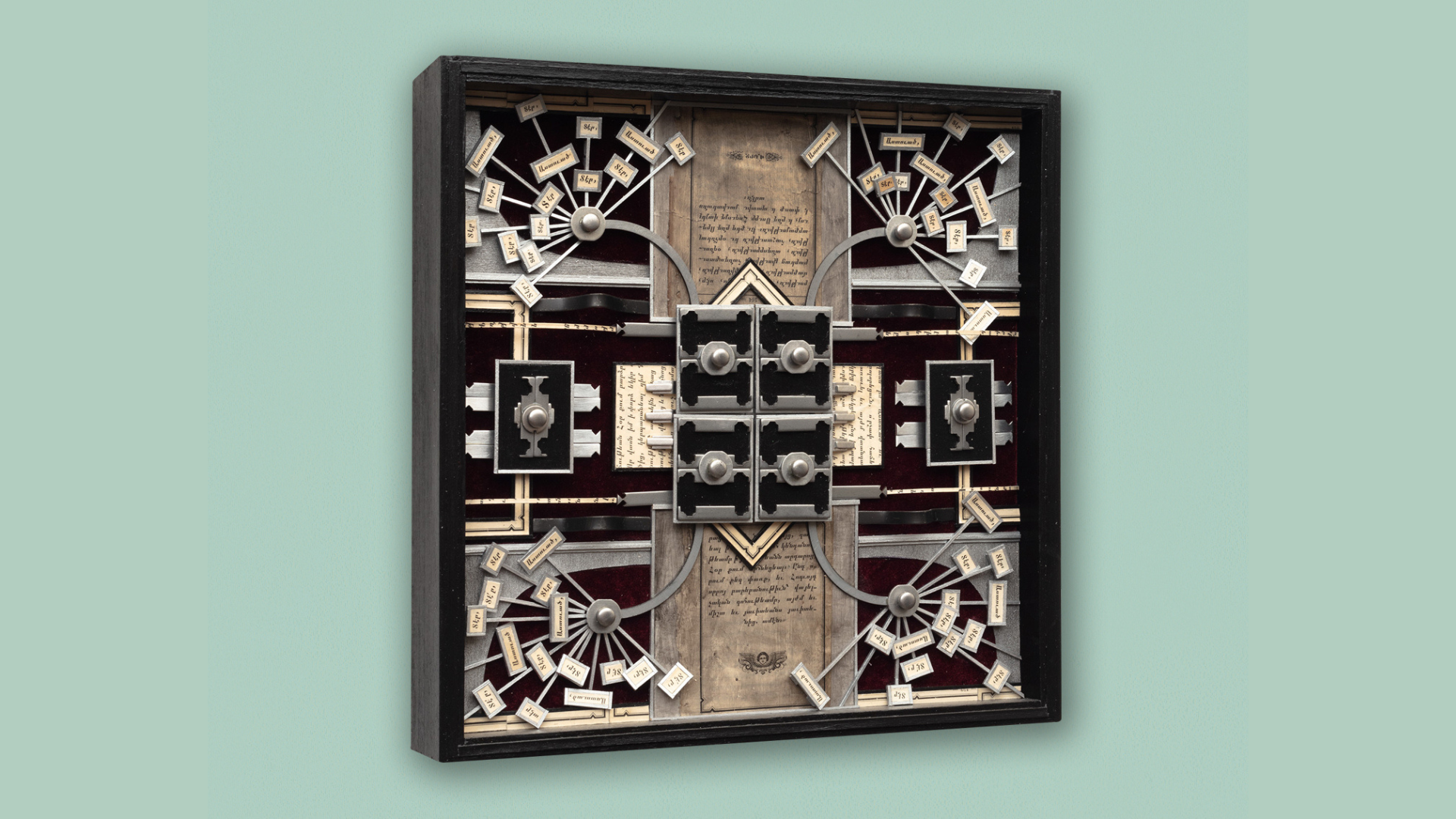

Artwork and text by Linda Ganjian

The Map of Her Prayers series serves as a memorial to my Yaya, an immigrant from Istanbul who was a sought-after seamstress, as well as fiercely devout. Inspired by ornate Eastern Orthodox medieval reliquaries, I map out prayers in her honor. I use reproductions from her prayer books and repeat certain words: “Lord,” “God,” and “Holy” (in Armenian) as a spiritual incantation. Other found and modeled elements related to her profession (velvet, pins, clay fabric/trim) complete my portrait of her. The structure of the prayer book itself becomes a newly-imagined architecture. Through composing and constructing, cutting and gluing, I invent a sacred, fantastical landscape as a way to channel my grief—creation as an antidote to loss.

Armenian Love

Artwork and text by Mariam Tamrazyan

My life far from Armenia was missing a special part of my youth, when I was surrounded by a joyful extended family where even the most trivial event would turn into a grand occasion to gather, feast, drink, sing, and toast to love and the blessing of family. It was also an excuse to dress up in our finest attire to celebrate the promise of newlyweds ready to start another loving Armenian family—their joy and great expectations flowing right from their hearts to ours.

These memories also take me back to a small kitchen infused with the sweet aroma of something baking in the oven and khoris and the sound of my granny rolling dough because one Gata was not enough; another impromptu get-together or festive celebration was surely on the way.

My art is inspired by the great Sergey Parajanov--the master of telling stories with found objects that conjure up sense memories embedded deep in the psyche, so personal yet universal in its humanity.

To view the works of Mariam Tamrazyan go to her Instagram @voskeyeraz.